Carbon pricing drives innovation. Here’s how.

By Dr. Philip Harding, CCL Economics Policy Network

It seems that every advancement in our collective understanding of climate science darkens the picture: warmer temperatures, shorter time frames, and broader impacts. Happily, the opposite seems to be true in our economic understanding of climate solutions, specifically a fee and dividend approach to pricing CO2 emissions.

A recent example of that is the paper by Joe Kennedy of Information Technologies & Innovation Foundation (ITIF) entitled, “How Induced Innovation Lowers the Cost of a Carbon Tax.” The key takeaway for CCL volunteers is that reducing emissions using a carbon price is cheaper than economic models have predicted, largely due to “induced innovation” driven by market forces.

How we got here

Kennedy begins by nicely summarizing the “market failure” that is the fossil fuel role in climate change, breaking it down into the realities that (1) fossil fuel is inexpensive, (2) alternative technology development is slow, and (3) we have implicit biases from the historical relationship between fossil fuel use and economic growth. The result is climate change, with relatively few market forces to counter it. This “how we got here” piece sets the stage for evaluating solutions and, for this reviewer, strengthens the case for a fee and dividend model.

Another element of the paper that is potentially useful for CCL advocates is a succinct portrayal of technology research and development (R&D) and adoption by companies. Kennedy describes the steps of invention, innovation, and diffusion; where invention is creating something unique, innovation is figuring out how to mass produce and/or bring the technology to market, and diffusion is the final step of widespread technology acceptance and adoption.

How innovation happens

The paper describes three mechanisms by which innovation happens. The evolutionary approach to R&D says companies are risk averse and only invest in innovation to keep up with the competition. There is a randomness associated with which technologies succeed and expand. An example could be a company that developed a technology to support a VHS (versus beta) video.

The path dependence theory assumes that technologies get “locked in” and keep new ideas out because the risk in changing direction takes too much capital to overcome. An example of this might be an electric car charging plug design; once companies have adopted it, they are unlikely to switch to another design even if it’s much better.

The third theory, which Kennedy suggests is underappreciated, is induced innovation, where market forces compel businesses to innovate, keep product costs down, and maximize profits. If a price on some factor of production increases, e.g. fossil fuel cost, invention and investment will be spurred and technology change will happen. The CCL fee and dividend strategy will make induced innovation happen.

Inducing innovation through carbon pricing

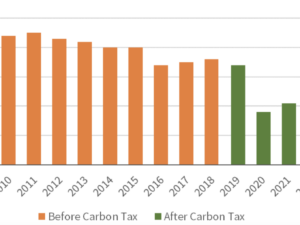

Kennedy proposes three attributes necessary to induce innovation through a carbon pricing program. It must have certainty (or predictability for business), be comprehensive (to enable public support), and have border adjustments. He then reviews several relevant examples to support carbon pricing’s positive influence on induced innovation, with selected citations following here. Popp and Newell demonstrated that carbon pricing increases patenting activity, but also that carbon pricing that is too low may have little or no effect on emissions. Newell et al. demonstrated that product energy efficiencies increase as energy prices increase or energy use is regulated, e.g. hot water heaters. Calel showed that carbon pricing increases patent activity, but also described a “crowding in” phenomenon where companies race to invest in alternative energy technologies with unexpected positive consequences.

Kennedy then discusses the variety of ways in which the revenue from carbon pricing could be used, from deficit reduction to cutting taxes to increasing government spending, with only a passing reference to a dividend approach. He chooses not to discuss the political vulnerabilities of the different approaches nor to relate them to his criteria of program comprehensiveness.

It is worth noting that Kennedy likely has the interests of the technology industry in mind. ITIF is a nonprofit, nonpartisan public policy think tank. Review of its board members and funding sources suggests that the organization is not driven by companies in energy sectors, but rather by IT companies such as Google, eBay, Intel, Intuit, and Hewlett-Packard Enterprises. Not surprisingly, he ends up recommending using the revenues to provide to companies “subsidies for R&D and capital equipment investment.” So, Google can use that money to develop new smartphone applications. Even more perversely, an energy company with a short-term view could use their R&D tax subsidy to investigate more efficient ways to extract crude oil from deep-water wells before carbon prices increase too much, and do this on the backs of consumers who will absorb much of the carbon price.

The CCL carbon fee and dividend strategy returns revenues to individuals. The genius of this approach is that, through recycling money back into the hands of consumers, it turbocharges the economic forces and presents individuals and companies with new ways to make money. Be it an attic insulation business, software to increase electric car range, or long-term alternative energy development, there are virtually thousands of ways that carbon fee and dividend would accelerate and unlock a clean energy economy.

Identify a carbon-intensive object or activity, and ask yourself: What thrilling opportunities will present themselves with a carbon fee and dividend? I presented this thought experiment in a Citizens’ Climate University webinar this past fall and invite all CCL members to share their examples on CCL’s Forums. The more stories we share, the more powerful our advocacy will be in highlighting the transformation awaiting our economy. Carbon fee and dividend will create myriad market opportunities. Let’s let individuals and companies earn their revenue.

Philip Harding holds a Ph.D. in chemical engineering, has 15 years of industry experience, and serves as the Linus Pauling Chair in chemical engineering at Oregon State University.

The Economics Policy Network is a team of CCL leaders and supporters with a diverse background in the field of economics. These network contributors write regular guest posts, offering thorough insight into topics that fall within their expertise. Their resources are available in the form of white papers on CCL Community.